Educators as social caregivers and the importance of our wellbeing during the confinement and beyond

By Lola Reeves Garay-Abad

Personally, the coronavirus pandemic has made me question many aspects of my own practice as a teacher and a teacher trainer. Despite having been in education for almost 20 years, there have been plenty of times when I felt I am starting all over again, back to being 17 and stepping into a classroom for the first time, full of uncertainty and doubt, wondering if I am up to the task. Such moments of uncertainty and vulnerability are a necessary evil and have made me reflect on our wellbeing as educators during the pandemic and beyond.

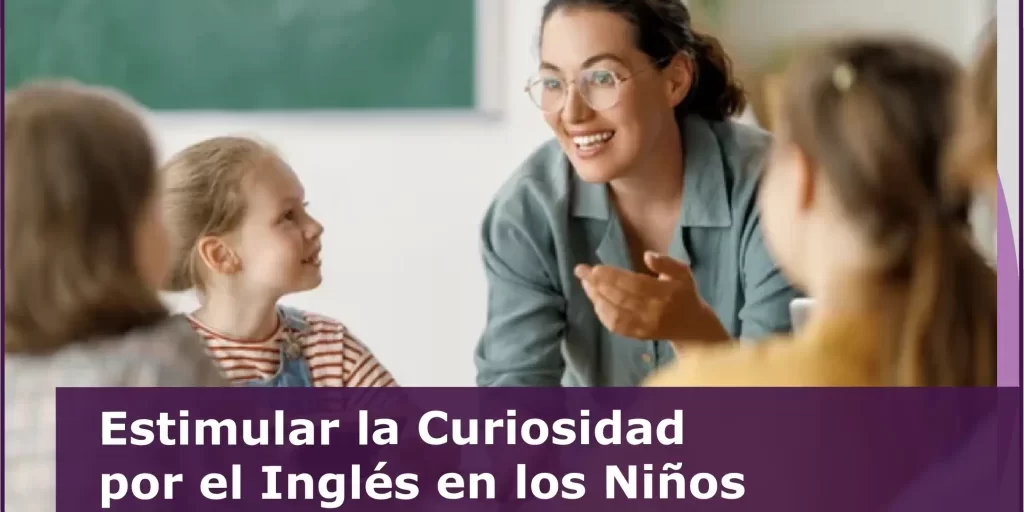

When we think about our wellbeing, we think about coping mechanisms and positive thinking to keep our spirits up in challenging times. However, there is a deeper concept behind keeping our spirits up, it is keeping ourselves aware and conscious of our needs and vulnerabilities in order to build resilience. In that respect, the confinement has been a testing time for us as educators, during which we have had to face a sudden change in our routine and our approach to teaching. We have also had to re-evaluate our emotional needs as social caregivers, accept uncertainty, and understand that our vulnerabilities are not weaknesses, but on the contrary, the source of courage.

According to research, a social caregiver is anyone who is involved in the wellbeing of another individual. We, as educators, are social caregivers, and take on a committed responsibility for another person’s development, we are involved in the creation of a connected society, as well as being receptive to emotional needs from families and learners, in short, we co-parent. Having such role involves developing mechanisms to build resilience in challenging times such as the pandemic and beyond, which leads me to ask: How are our social systems facilitating teachers’ wellbeing and skills to build resilience?

Well, it starts in our educational community of families, learners and school leaders. In my experience as an educational mentor and school leader, there are small changes we can make to help educators build resilience and improve our emotional wellbeing. The confinement has led to a psycho-social reorganization of time and space; we have not been able to switch physical spaces to delimit the end of a school day and the beginning of the rest of our living routines. We have not only had to work at home but work with home. Therefore, putting in place strategies such as well-established timetables and specific boundaries has been necessary to turn such invisible delimitation of time and space into a visible, tangible structure.

Such strategies include, for instance, scheduling beginning and ending times for classes, for replying to students’ emails, for marking, for replying to parents’ messages, and for team meetings. Availability and generosity of time do not mean lack of limits; turning our messaging systems off after 7:00 pm does not mean being careless towards the needs of our students/families/institution at 8:00 pm, but on the contrary, it means that we are taking care of ourselves as social caregivers and as mentors, in order to be more focused, effective and efficient in the long-term. It also means helping our students understand the meaning of respect, boundaries and where a person’s rights and duties end and theirs begin. We are trying to help them develop organizational, social skills and empathy, therefore, establishing healthy boundaries sets an example for them.

Other strategies include taking regular mini “brain breaks”, such as doing a 10-minute breathing exercise; creating short-term to do lists, using highlighters to underline priorities; taking proper meal breaks; choosing an activity we like and that we can do from home and schedule such activity in our timetable, if not every day, every couple of days or so, and getting progressively into a routine; among others. At a deeper level comes the understanding and analysis of the fine line that exists between being busy and being stressed out and how we manage stressors. It is also important to identify who we can talk to and complain/moan with, ideally someone who will not judge us, but will listen to us with empathy and not sympathy. It is also important to remember and understand that generosity minus limits equals resentment, a concept that should be present in the caregiver and the care-receiver’s actions.

As school leaders, one of our social responsibilities is to be able to recognize such needs and vulnerabilities in our team, so that we can take the role of a mentor. It is all about caring for the caregiver, including ourselves. It is also about taking a non-judgmental vision towards our team’s vulnerabilities since there is no mentoring process when judgement is present. Understanding our team’s timetables and boundaries and making families aware of them as a sign of mutual respect will help reach a common ground of what we can do as a social group towards the well-being of educators.

There are several aspects I hold myself accountable for from a management position, which help me be conscious of my team’s needs:

- Do I understand the limit and difference between giving information and overloading my team with information?

- Am I moderating meetings efficiently and therefore, practicing empathy? Could I send an email about certain aspects instead?

- Am I being approachable and holding small feedback meetings with my teams?

- Am I offering quality of time and not just quantity of time?

- Can I hold myself and my team accountable without shaming them or feeling ashamed?

- Am I ready to sit next to them, rather than across from them and put the challenge in front of us rather than between us (or sliding it toward them)?

- Am I ready to listen, ask questions, and accept that I may not fully understand the issue at hand?

- Can I recognize my team’s strengths and how I can use them to address their challenges?

- Am I open to owning my part when an issue arises, and be non-judgemental towards myself and my team?

- Can I model the vulnerability and openness that I expect to see in them?

We are all in this together and we do not get it right all the time. It is ok, the best we can do is keep ourselves conscious and aware of our needs and vulnerabilities as a social group and as social caregivers. It is necessary to incorporate such awareness as part of our emotional well-being in order to build resilience during challenging times.

Artículo Fuente: La Vanguardia

La pandemia provocada por el coronavirus ha supuesto un reto para todos, especialmente durante las semanas de confinamiento en las que nos hemos tenido que adaptar a una nueva situación. Convivir muchas horas en familia y adaptarnos a trabajar o estudiar desde casa no han sido tareas fáciles. Tampoco para los profesionales de la educación ha sido una situación sencilla.

Tal y como explica Lola Reeves Garay-Abad, de Trinity College London, “la pandemia de coronavirus me ha hecho cuestionar muchos aspectos de mi propia práctica como docente y formadora de docentes. A pesar de haber trabajado en el sector de la educación durante casi 20 años, ha habido muchas ocasiones en las que sentí que estaba empezando de nuevo, volviendo a tener 17 años y entrando en una aula por primera vez, llena de incertidumbre y dudas, preguntándome si estaba a la altura de la tarea”, explica.

Esta situación de incertidumbre y vulnerabilidad ha llevado a esta profesora a reflexionar sobre el bienestar de los educadores durante la pandemia. “El confinamiento ha sido un tiempo de prueba para nosotros como educadores, durante el cual hemos tenido que enfrentar un cambio repentino en nuestra rutina y nuestro enfoque de la enseñanza. También hemos tenido que reevaluar nuestras necesidades emocionales como cuidadores sociales, aceptar la incertidumbre y comprender que nuestras vulnerabilidades no son debilidades, sino, por el contrario, son fuente de coraje”, reflexiona.

Un oficio con responsabilidad

Un cuidador social es cualquier persona involucrada en el bienestar de otra persona. También los profesores y educadores, “somos cuidadores sociales”, dice la docente, ya que asumen una responsabilidad con el desarrollo de otra persona. Además, están involucrados en la creación de una sociedad conectada y son receptivos a las necesidades emocionales de las familias y los alumnos. “Ese papel implica cultivar mecanismos para desarrollar la resiliencia en tiempos difíciles como la pandemia”, afirma la profesora.

Reeves considera que hay pequeños cambios que podemos hacer para ayudar a los educadores a construir resiliencia y mejorar su bienestar emocional. Por ejemplo, establecer estrategias tales como horarios bien pautados y límites específicos para convertir esa delimitación invisible del tiempo y el espacio en una estructura visible y tangible.

También programar horarios de inicio y finalización para las clases, para responder a los correos electrónicos de los estudiantes, para responder a los mensajes de los padres y para las reuniones de equipo.

La disponibilidad y la generosidad del tiempo no significa no poner límites. “Apagar nuestros sistemas de mensajería después de las 7 de la tarde no significa ser descuidado con las necesidades de nuestros estudiantes, sino que significa que nos estamos cuidando como cuidadores sociales y mentores para estar más centrados y ser más efectivos y eficientes a largo plazo”, comenta la profesora.

“También significa ayudar a nuestros estudiantes a comprender el significado del respeto, los límites y dónde terminan y comienzan los derechos y deberes de una persona. Estamos tratando de ayudarlos a desarrollar habilidades organizativas, sociales y empatía, por lo tanto, establecer límites saludables es un buen ejemplo para ellos”, añade.

Otras estrategias incluyen tomar pequeños “descansos cerebrales” regularmente, como hacer un ejercicio de respiración de 10 minutos; crear listas de tareas a corto plazo, usar marcadores para subrayar prioridades; tomar descansos de comida adecuados; elegir una actividad que nos guste y que podamos hacer desde casa y programar dicha actividad en nuestro horario, si no todos los días, cada dos días más o menos, y convertirla en una rutina, entre otros consejos.

En un nivel más profundo llega la comprensión y el análisis de la delgada línea que existe entre estar ocupado y estar estresado, y cómo manejamos este estrés. También es importante identificar con quién podemos hablar y quejarnos, alguien que nos escuche con empatía.

Testimonios

¿Quieres recibir nuestro Newsletter, promociones y acceso a talleres exclusivos?